Reading time: About 7 minutes

Trigger Warning: The atrocities of the Holocaust are mentioned in this article.

Life can unfold so quickly, especially when we’re young. In just five short years—from my first trip to Germany at 17 in 1988 to living on my own as an adult in 1993—I transformed from an inexperienced teenager into a seasoned traveler. During that same period, on a grander scale, the Berlin Wall fell, and Germany moved from division to unity. These changes remind me of how our personal journeys unfold alongside historical ones, each shaping us in ways we don’t fully realize until later.

This past September, I returned to Northern Germany, the birthplace of my first international experience. My husband Mike, his mom Lucy, his sister Barb, and I embarked on a river cruise with Vegan Cruises & Tours, traveling from Hamburg to Berlin.

Standing at the ferry terminal as the Elbe River sparkled in the September sun, nostalgia washed over me. I thought back to my teenage adventures in Northern Germany—just a year before the Berlin Wall came down! So much has changed since then. The once gritty warehouse district is now a vibrant cultural hotspot, blending old-world charm with fresh, modern energy. It was the same place, yet somehow, it felt like I was seeing it for the first time.

In many ways, it’s the same for me. I’m still me, the person I was 36 years ago, but I, too, have changed so much over the years. My experiences in Germany in those formative years are part of what made me who I am today.

From Innocence to Awareness

Back in 1988, my impression of Germany was set against a divided nation, split after World War II by competing ideologies: Western democracy versus Soviet communism. This division had been carved from the horrors of a war in which millions lost their lives, most of them innocent victims of the Nazi regime.

My German host family did not shy away from this history. During my stay, they took me to the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp Memorial. It wasn’t an easy visit. For starters, Bergen-Belsen is where Anne Frank died. I read her diary when I was 13—the same age she was when she began writing. Anne’s story is one reason I write about my life today. She was one of thousands who died there, and the mounds over the mass graves are stark evidence of that loss.

Though young and sheltered, I grasped enough to feel the gravity of what I was seeing. Anne Frank’s last days were spent starving and dying of typhus fever, a disease that causes intense muscle pains, nausea, and delirium. Thousands died of typhus in Bergen-Belsen, and the camp was liberated about a month after Anne’s death. This tragedy struck me deeply then and has stayed with me ever since.

Since 1988, I’ve learned more about the Nazis, their hate-fueled agenda, and their systematic approach to mass murder. Visiting Auschwitz in 2006, I was horrified to learn of the medical experiments they did on Jews and other prisoners. We were shown fabrics made from human hair shorn from their victims. It was all very systematic, similar to the way we slaughter animals and use their hair and skin for things we wear. This is how the Nazis saw Jews, people with disabilities, queer people, and anyone else who didn’t fit their ideal Aryan stereotype. They were not seen as humans but as creatures to be exterminated and, where possible, harvested. It was terrifying evidence of evil at its most industrialized and inhumane.

Keep this in mind when you hear others speak about a group of people—any group of people, especially those you disagree with—as “those people.” Generalizations lead to demonization. Demonization leads to average ordinary people accepting inhumane acts and mass murder.

Stumbling Over Memories

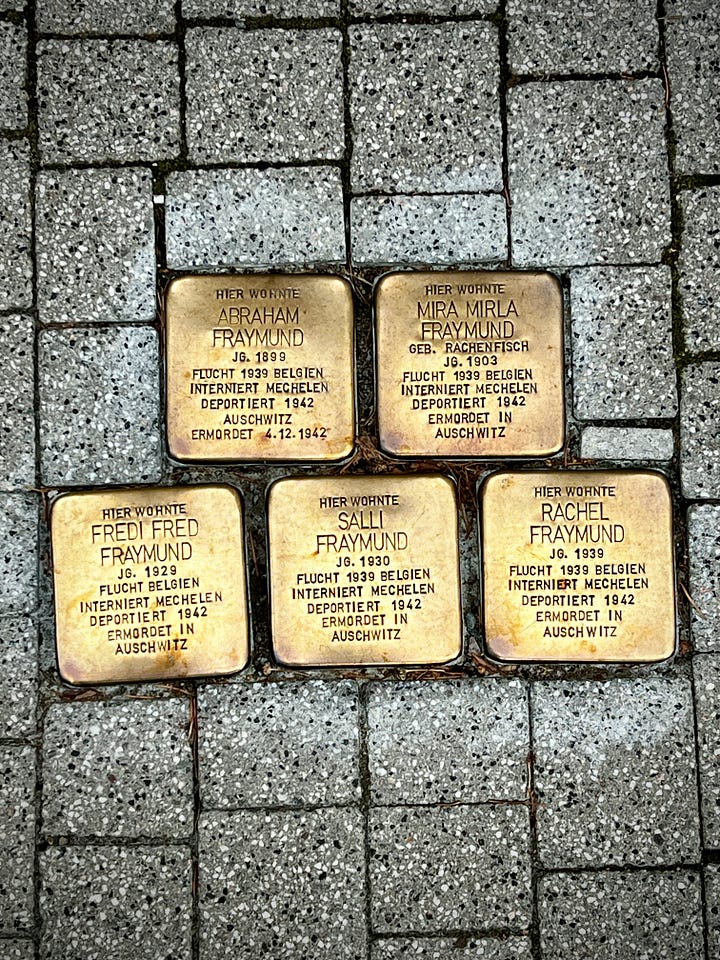

During our recent cruise, I came across small bronze squares embedded in the sidewalks of towns we visited. These squares had names and dates from the Nazi era, with familiar, harrowing words like “Auschwitz.” I didn’t need to understand German to grasp the horrors they represented.

Later, I learned these are stolpersteine, or “stumbling stones.” Their purpose is as symbolic as it is literal—their polished surface catches the eye, causing passersby to “stumble” and bow slightly to read the inscription. Each stone represents a person taken or driven away from that very spot. The stones I saw marked the sidewalks in front of houses and apartments, reminders that people were torn from the very places where I now stood.

Each plaque begins, “Here lived,” followed by the person’s name, birth date, and fate: internment, exile, suicide, or, tragically often, deportation and murder. Craftsman Michael Friedrichs-Friedländer handcrafts each plaque, and there are over 70,000 stolpersteine worldwide.

There could be millions more, including ones for my husband’s maternal grandparents and his aunts, who were forced from their home in Poland to a work camp near Stuttgart. My mother-in-law was born in that camp. They were not Jewish; they were Catholic Poles. The Third Reich’s goal to “Make Poland German Again” involved deporting and exterminating non-Germans or enslaving them as laborers until they were no longer useful.

My in-laws were lucky. They survived the war and were eventually liberated, but they emerged as “Displaced People”—without a country. Unable to return to Poland, they spent years waiting for a new homeland before emigrating to the United States.

Witnessing the Wounds

In Berlin, reminders of this dark past are woven into the very fabric of the city. Monuments honor the millions of Holocaust victims, while traces of battle scars remain on World War II-era buildings. Look up, and you’ll see the pockmarks left by bullets and explosions as Allied troops stormed Berlin, fighting to end Nazi rule. Many soldiers survived, but thousands gave their lives in the process.

Käthe Kollwitz’s sculpture Pietà (Mother with Dead Son), created between the world wars, captures the profound loss of a mother grieving a son lost to battle. The inscription below reads, “To the victims of war and tyranny”—a stark reminder of the lives crushed and impacted by war.

On our last day in Berlin, we retraced the rise and fall of Hitler and the Third Reich. History met a poetic turn as a cruel dictator, who saw himself above all laws of humanity, ultimately perished almost entirely alone in an underground bunker. Now, that bunker is a simple parking lot, where cars pass over it daily, indifferent to the site’s former infamy.

Just down the street, though, lies an impressive memorial--Berlin’s Holocaust Memorial, designed by Peter Eisenman. It stretches across an area the size of four football fields. Giant gray concrete slabs, some tall and straight, others tilting, create a labyrinth. Walking through, you can look up and see the sky, but straight ahead feels disorienting, even claustrophobic. This unsettling layout is intentional—a physical reflection of the confusion, fear, and despair endured by Europe’s Jews during the Nazi era.

Stepping Across Time

In these last moments in Berlin, I felt a powerful sense of coming full circle. In 1988, I had stood behind the Brandenburg Gate, limited to one side of a wall that divided Berlin. Even then, I felt the weight of history and the fear for those on the other side. Never could I have imagined that one day, I’d stand on the other side of that gate with my mother-in-law—the same woman born in a Nazi work camp nearly 80 years ago. Time had carried us across decades and continents, and in this quiet moment, I felt both the resilience of history and the privilege of witnessing its transformation.

What a beautiful and important reminder of where we've been, and where we ought never return.

What a touching story. This is my first time hearing of Stolpersteinen. So moving. Thank you for telling us. I am reminded of the saying, “If we don’t know history, we are doomed to repeat it.” It seems rather apropos of our current moment. BY the way, I’m still burning my Kamala candle & im going to keep refilling it and keep it going. XXOO